Standard 12/1 mbps plan could rise to over $150 if pricing model doesn’t drastically change

Despite the debate about technology used, the cost of NBN’s CVC remains the single biggest threat to the NBN’s success.

While the availability of high-speed, unlimited broadband grows in developed nations around the world, the future of “unlimited broadband” in Australia is becoming increasingly bleak. The use of applications requiring greater amounts of bandwidth grow in households is partially to blame, but the country transitions to the NBN – the way nbn designs their pricing structure will also be increasingly important. Currently, the NBN pricing structure is far too cost prohibitive for the amount of traffic the network is designed to carry.

What is this CVC thing?

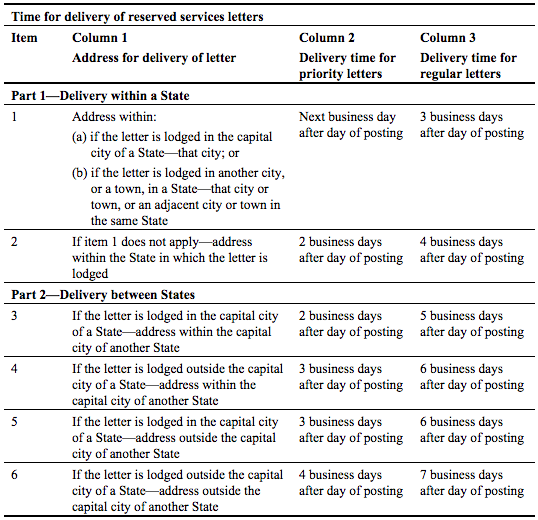

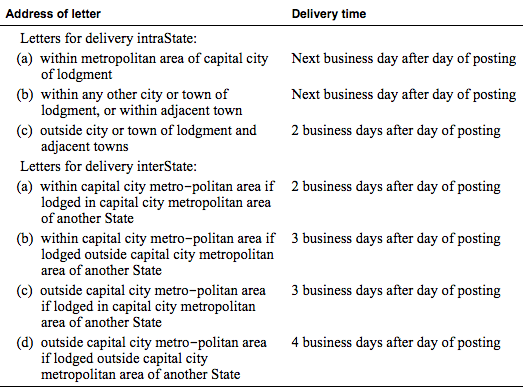

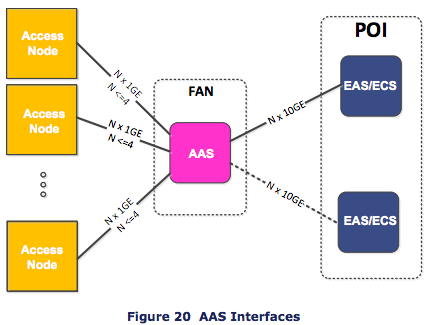

Connectivity Virtual Circuit (CVC) is a virtual charge imposed by NBN to service providers to offload your traffic from the NBN network into the service provider’s network. After a discount introduced at the start of the year, NBN charges $17.50 per Mbps of traffic shared across the ISP’s customer base. Initially, the cost was $20 per Mbps.

This is in addition to the cost of physical interconnect connection between the provider and NBN (called the Network-Network Interface, NNI) plus the cost that NBN charges for the link between your home and NBN’s point of interconnect (known as the Access Virtual Circuit and User-Network Interface, AVC/UNI).

The Netflix effect

It became pretty obvious after the launch of Netflix in Australia that the current pricing structure is unsustainable. With the high-bandwidth of the NBN, customers expect to stream movies and TV shows with plenty of remaining capacity to do additional work in the background.

To be able to deliver a HD stream, Netflix recommends 5Mbps of bandwidth. To be able to guarantee at least a single stream to every household, ISPs need to purchase 5Mbps of CVC per household:

$17.50 × 5 Mbps = $87.50

This neglects costs like the actual cost of connecting you to the Internet (Backhaul/IX costs) and link between your home and NBN’s point of interconnect – which start at $24 for 12/1 Mbps. Backhaul and IX costs depend on the ISP’s deals with backhaul providers and the volume they have – but consider $10 per mbps a reasonably conservative estimate. So, for a typical 12/1 connection that can consistently deliver at least 5 Mbps:

| Cost element |

Cost |

| CVC – 5 Mbps |

$87.50 |

| AVC/UNI – 12/1 Mbps |

$24.00 |

| Backhaul/IX Costs – 5 Mbps |

$50.00 |

| Total |

$161.50 |

Since a typical 12/1 NBN plan costs far less than the $161.50, you can understand where the compromise lies – CVC, IX and backhaul.

While you wouldn’t necessarily expect that all users will simultaneously watch Netflix at the same time, the number of simultaneous streamers is growing exponentially. ISPs also need to prepare for “extraordinary” events like when Netflix released the entire season of Orange is the New Black – a far greater proportion of users will be watching Netflix at the same time for an extended period of time.

Future of small providers

With the high CVC costs, small providers will find it increasingly hard to compete with larger providers like Telstra, Optus, iiNet and TPG. These providers either have enough traffic volume (or own their own backhaul infrastructure) to lower costs in the backhaul or IX component to offset the high CVC.

Smaller providers still need to “rent” capacity from backhaul infrastructure providers such as Telstra, AAPT, PIPE and Nextgen Networks. With even large providers like iiNet feeling the pinch, it’s no wonder that smaller ISPs are beginning to struggle. Even with the scale of a large customer base, current consumer cost expectations are simply unsustainable.

What’s a solution?

nbn™ could continue dropping the CVC charge as demand increases, however, it faces the risk that service providers will continue to skimp out on CVC – thus lowering revenue.

The good news is the company has also begin conducting a second round of industry consultation to help overcome the problem.

For me, one solution I can see feasible, is to replace the CVC cost with a standard capacity charge (which guarantees a certain ratio of CVC to AVC) comparable to current industry contribution to CVC per user. Then, provide capacity boosts for users and applications that require a greater capacity. This guarantees “minimum” revenue for nbn™ and increases capacity to suitable levels for service providers.

Alternatively, I could see increasing the user-connect costs (AVC/UNI) and drastically cutting CVC costs as a possible solution. This would also guarantee revenue to a certain extent, while retaining the control of contention with service providers.

Whatever happens, the nbn™ pricing model needs to change drastically in order for Australia to remain competitive in the 21st century. Otherwise, we’ll continue to be slowed down by a “virtual” cost-prohibitive charge by our nationwide broadband network.