4G/5G mobile growth will not undermine the NBN business case. It should actually help boost NBN revenue.

(opinion) Phone towers aren’t magical. They need to be connected back to a datacentre in order to process calls, send texts and most importantly — connect you to the Internet.

There’s no doubt that one of the greatest cost barriers for mobile phone companies to increase coverage is the cost of backhaul to mobile phone towers.

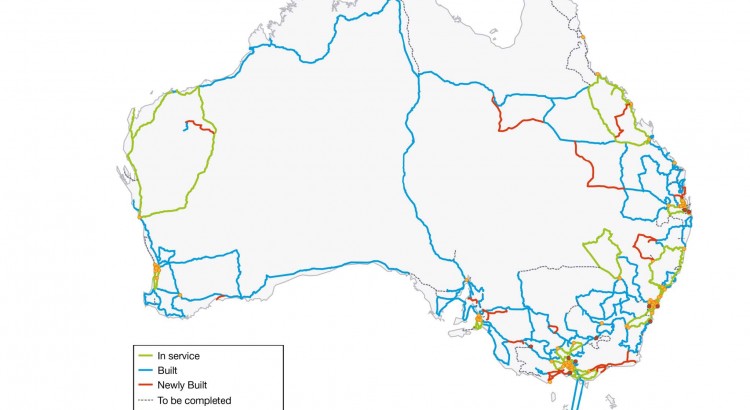

Telstra has always had a natural advantage in the mobile coverage race due to its extensive fibre network laid out between its telephone exchanges. Optus is not too far behind, but certainly lacks the robust network Telstra has especially in rural areas.

But let’s think for a moment about Vodafone, or potentially a theoretical fourth national mobile carrier which may or may not start with the letters TPG. The National Broadband Network can play an extraordinary role in helping these companies not only expand their network coverage size, but also create denser and higher bandwidth coverage to ease congestion.

Dark fibre vs managed services

Traditionally, a carrier may opt to roll out their own fibre to a tower — but that could come at a huge capital cost which may not be viable for carriers with comparatively lower subscribers.

Alternatively, they may rent dark fibre or purchase a managed transit service from the likes of Telstra or Optus and pay back a recurring fee for the amount of bandwidth they want delivered through the service. Unfortunately this means even if only a small number of customers are connected to a tower at a given time, the carrier would have to pay for the full bandwidth they’d purchased from their transit provider.

How the NBN could change the game

But the NBN could change all that, and this could mean enormous transit cost savings for leaner carriers who don’t own as much transit network infrastructure.

Early last year, the company revealed that it began conducting trials for “Cell Site Access” — giving mobile carriers like Vodafone access to the National Broadband Network to connect towers.

AVC+CVC works well for mobile transit

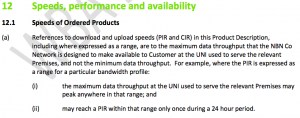

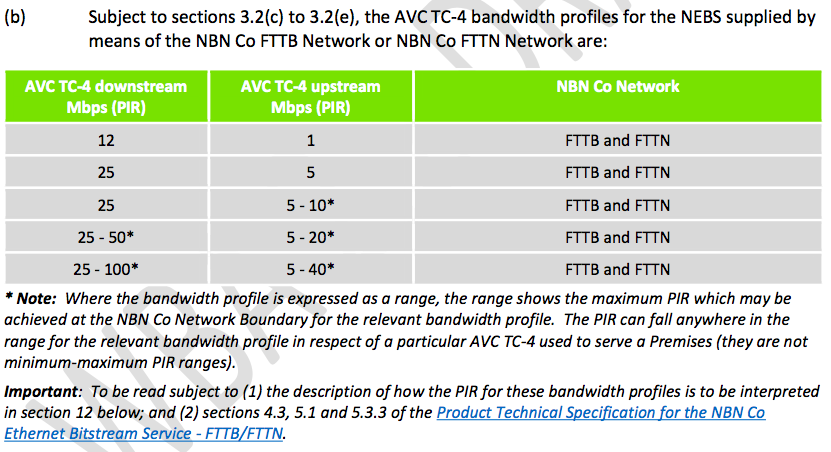

The two-part access and connectivity charge (AVC+CVC) that nbn currently uses means that the carrier can pay for a relatively low cost for a high bandwidth Access Virtual Circuit (say 100+ Mbps) at the tower but only pay for the bandwidth at a regional level (Connectivity Serving Area, CSA) at the point of interconnect (POI).

This means that no matter how many towers they put up, as long as the overall bandwidth that gets transferred across the mobile network doesn’t change, there will only be a minimal cost difference in terms of transit between towers.

Of course, the equipment costs will still exist — but carriers could increase their cell density in a metropolitan area or regional centres by installing small “towers”, but only have to pay some $40 in monthly cost for connecting the towers to the NBN Point of Interconnect.

Great for dealing with peak demand at venues

The flexibility of the two-tier AVC-CVC model for mobile carriers means that if “mobs” of people aggregate at a particular location say for a sporting event — the carrier could simply increase the low-cost AVC component to cope with the peak demand at that particular location. That, of course, assumes that overall data consumption doesn’t increase which is probably not true from experience. But it means that carriers will not have to pay massive premiums for high-bandwidth transit during the entire year, when it can cater for occasional high demand by paying a little more in the access component over an NBN transit solution.

I think there is massive potential for NBN to shake up the mobile transit market. Once the NBN is built, the infrastructure will be there to support high density microcells in built up areas and also for carriers to expand their coverage in more regional areas at relatively low cost.

I guess the point I’m trying to make is that growth in mobile doesn’t necessarily undermine the NBN. 4G and 5G networks will still need high bandwidth transit to carry all that data from the tower back to the carrier’s data centres… and it seems the NBN is an obvious candidate for some carriers.

I’m really quite excited to see what mobile carriers may do in the future with the NBN, and I’m sure nbn wouldn’t mind having some extra revenue given current circumstances with the MTM cost blowout.